Happy September!

Your free demo this month is...

“What a Lark!”

Sign up to receive the song!

(Each month I send a free secret demo like this to my subscribers — you also get access to all the past songs I’ve sent out!)

(keep reading for more info on the song)

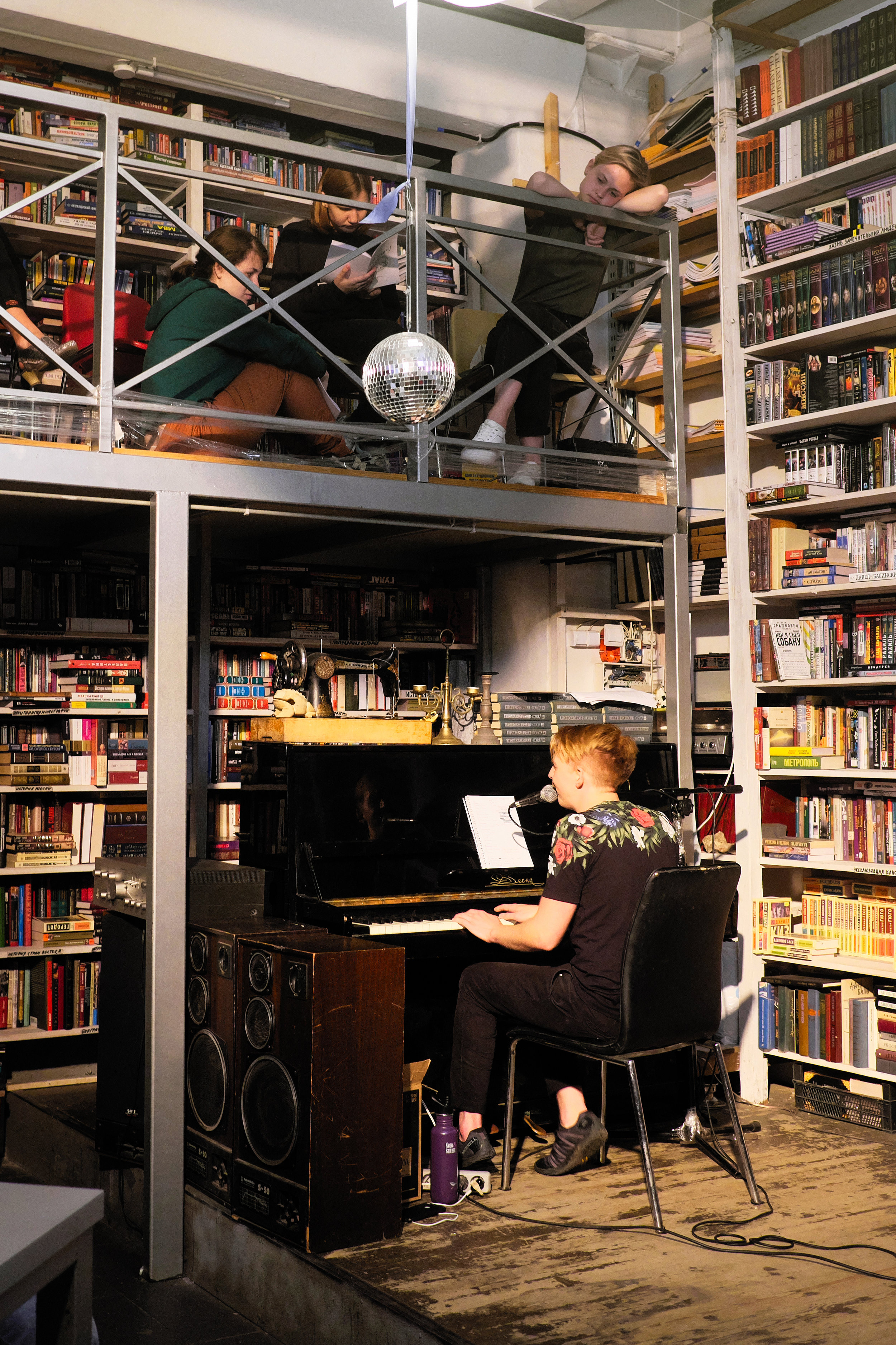

In August, I decided to take a little more time to breathe. I dug into some good books, played a couple shows at Hotel RL in Olympia, Washington, worked on recording demos, and wrote a huge blog post about my time in Kaliningrad on my tour back in June.

The song I’m sharing this month — “What a Lark!” — was inspired by my morning at the Baltic Sea on June 15th, which you can read about in the aforementioned blog post. I started writing it in London on my friend Jack’s piano, spent some time pondering over my audio notes in New York, then finished it up in Portland.

I was camping on the beach at the Baltic Sea with my Kaliningrad friends, absolutely all of whom are night owls. I, on the contrary, am a total lark. I managed to stay up until midnight the night before, and when I woke at dawn, everyone seemed to be just getting to bed. Unable to sleep in daylight even with an eye mask, I crawled out of the tent and greeted the morning.

I found myself in a small city of tents.

Everyone’s in Tent City

Sound asleep

The fire from the previous night was still burning, and my friend Seryozha sat next to it, staring into the middle distance. He’d arrived after I went to bed, and at some point burnt his hand in the fire. Now he couldn’t sleep because of the pain. He didn’t have painkillers, so he was soothing the injury by keeping his hand buried in the sand.

I gave him some Ibuprofen, and eventually he tried to get some more sleep. He retreated into his tent but left his arm hanging out and his hand buried.

In his absence, I watched a White Wagtail pecking through the sand, flinging it back and forth.

White Wagtail on the shores of

The Baltic Sea

Sifting through the sand

Wagtail, are you wagging at me?

I mused on my lark-ness, busily writing postcards as everyone slept. I thought about my constant need for clarity — “beautiful clarity,” to borrow a phrase from Russian poet Mikhail Kuzmin. What was the plan for the day? When would I find out the plan? What time would everyone wake up? What all did I need to be ready for?

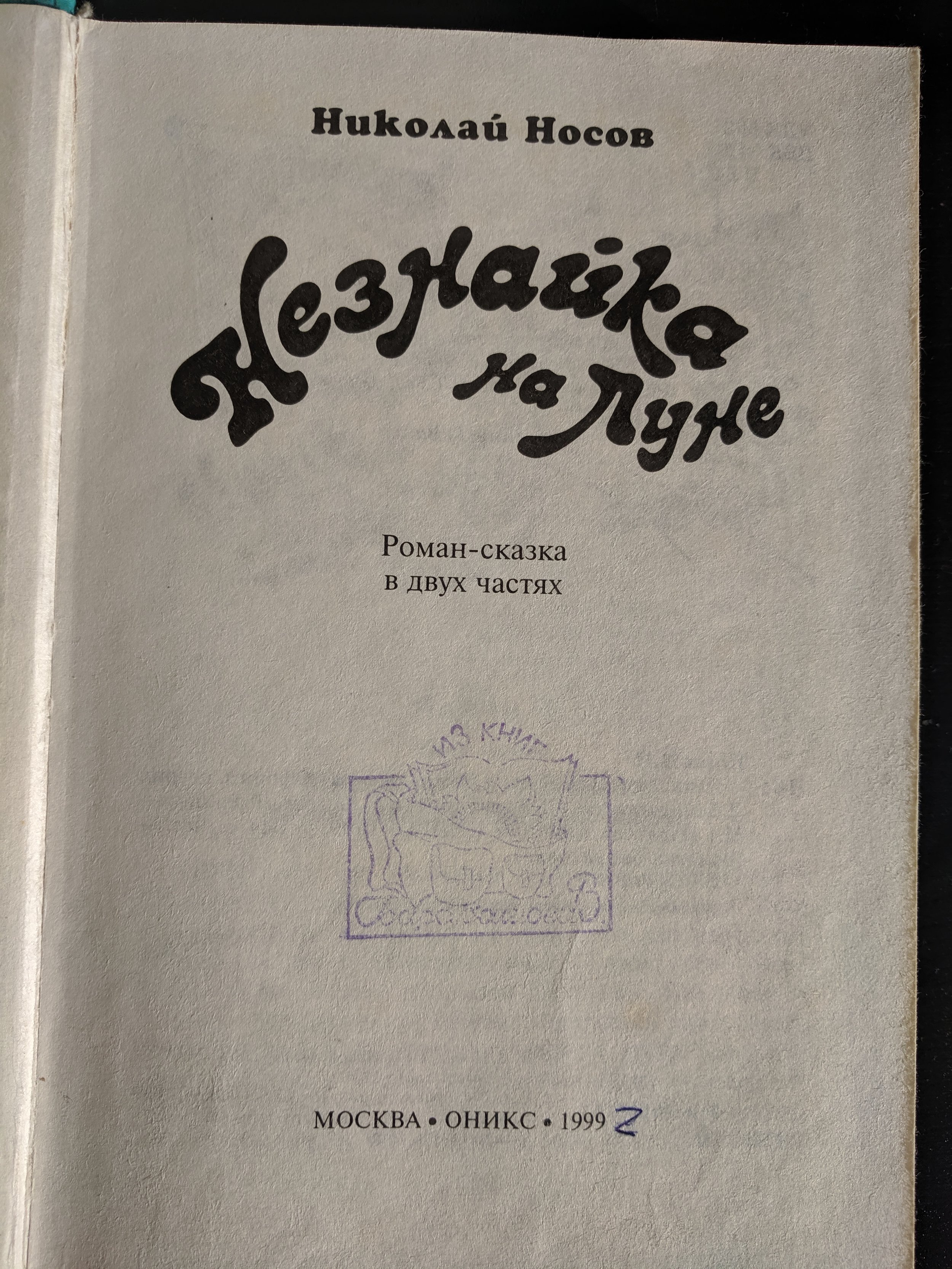

I thought a lot about my Kaliningrad friends. It’s strange to become so immersed in a community (not to mention a language and a culture) for a week, then to leave it all behind. Sitting alone on the beach, I marveled at the depth of my emotional connection to these people whose lives are so different from mine. I knew that there was nothing remotely similar waiting for me at home in Portland.

Most of the people in this tight-knit group met one another through theater. As morning progressed, individuals made entrances and exits: emerging from a tent, saying good morning, going for a quick swim, finding a place to pee, going back in the tent to continue sleeping. The action passed by like a dream, or an absurdist play about time. I couldn’t figure out what it all meant, but I knew that it was somehow beautiful, and that I would sorely miss being a part of it.

Actors in a play

Besides vocals, this recording includes piano, an additional keyboard voice, an ambient synth pad, and cello. As always, remember — this is a work in progress!

Thank you so much for letting me share new songs with you, and the stories behind the songs. And remember, I always like hearing from folks! You can email me, or reach out on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook.

Take care,

Stephan

Shows

September 14 - Hotel RL, Olympia, WA

September 28 - Sofar Sounds, Boston, MA

September 30 - Areté Venue and Gallery, New York City, NY

October 23 - McMenamins White Eagle Saloon, Portland, OR

November 25 - Yotsuya Tenmado Comfort, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan

November 26 - K.D. Hapon, Nagoya, Japan

November 28 - PEPPERLAND, Okayama, Japan

November 29 - LIVE rise SHUNAN, Shunan, Japan

December 2 - Graf, Fukuoka, Japan

December 4 - Risin’, Saga, Japan

December 5 or 6 - TBA, Ibusuki, Japan

December 9 - HOME, Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan

PS Do you want me to come to your city? Tell me and I’ll try to make it happen! (I don’t always know where people want me to go…) Also, if you’re curious about hosting a concert, it’s easier than you might think! Especially if you're in the US or Canada. Piece of cake.